1 什麼是 10 公尺行走測試?

10 公尺行走測試是一個簡單的檢查,主要用來看看一個人走路的速度有多快。

目的是快速了解受測者短距離走路的表現,功能性活動能力、步態和前庭功能。

例如長者的速度如果小於 0.7 m/s 或無法一次走完,代表走路速度太慢,容易跌倒,可能有肌少症。

2 10 公尺行走測試適合哪些人?

10 公尺行走測試可以用來評估各個年齡層的人,從小孩到老年人都適用,也適合用來評估以下疾病或狀況的患者:

- 神經系統疾病

- 腦性麻痺

- 多發性硬化症

- 帕金森氏症

- 脊髓損傷

- 中風

- 創傷性腦損傷

- 骨科相關

- 髖部骨折

- 下肢截肢

- 全髖關節和膝關節置換術

- 其他狀況

- 自然老化

- 運動障礙

- 唐氏症

3 10 公尺行走測試要怎麼做?

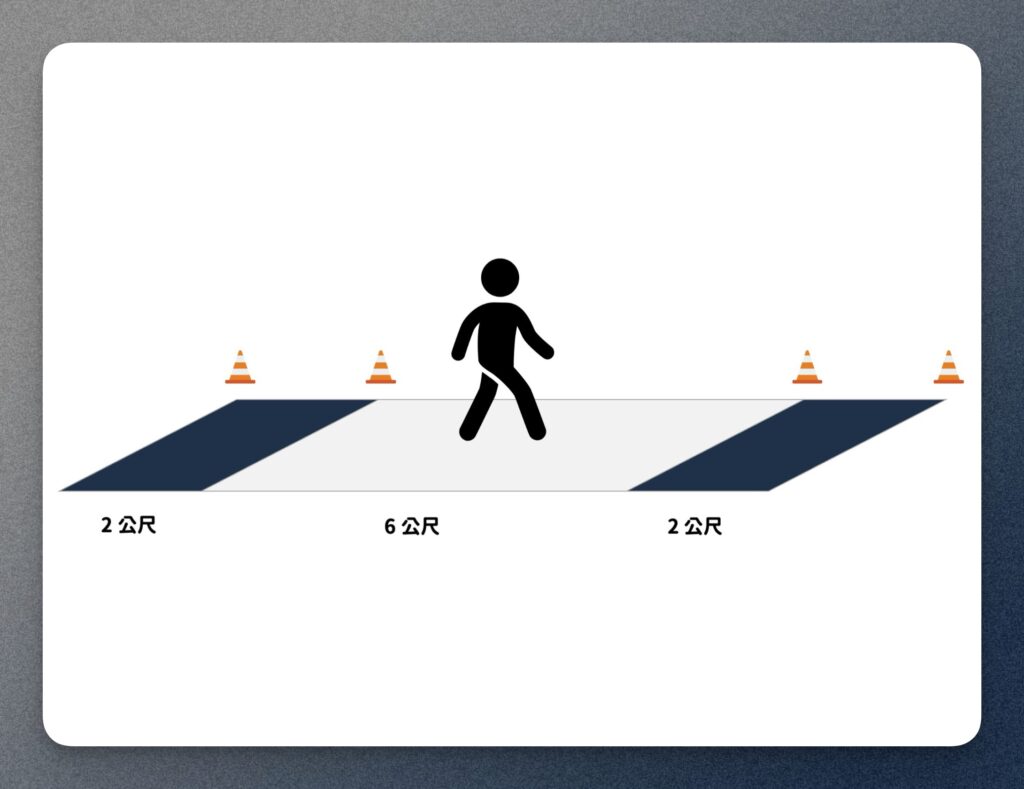

評估時,受測者要走完整個 10 公尺的距離,但只會計算中間 6 公尺的時間。

前面和後面各 2 公尺是讓受測者加速和減速用的。

測試時建議進行「一般走路速度」和「快速走路速度」兩種測試。

每一種速度都需要測試 2~3 次,然後算出平均值。

最後的速度會用每秒幾公尺(m/s)來記錄。

指導語

一般走路速度:

「用你平常覺得舒服的速度走路,走到終點標記時再停下來。」

“Walk at your own comfortable walking pace and stop when you reach the far mark.”

快速走路速度:

「用你最快但安全的速度走路,走到終點標記時再停下來。」

“Walk as fast as you can safely walk and stop when you reach the far mark.”

設備

- 秒錶

- 10 公尺的平坦、硬質地面,長至少 10 公尺(32.8 英尺)

- 確保受測者穿著舒適的鞋子。

- 如果受測者平常走路需要拐杖或垂足板等輔具,測試時也可以使用這些輔具。

場地準備

- 測量並標記起點(0 公尺)與終點(10 公尺)。

- 在測試區的開始(2公尺)和結束(8公尺)處各放一個標記,這樣就能清楚知道要計時的 6 公尺範圍在哪裡。

評估流程

- 說明評估流程:向受測者說明測試步驟,包括他們需要以兩種速度走 10 公尺,但只有中間的 6 公尺會被計時。

- 讓受測者練習:讓受測者先練習幾次,熟悉走路距離和起點與終點的位置。

- 開始測試:讓受測者站在 0 公尺標記處,並指示他們準備開始步行。

- 開始計時:當受測者的腳尖越過 2 公尺標記時,啟動計時器。

- 停止計時:當受測者的腳尖越過 8 公尺標記時,停止計時器。

- 記錄時間:記錄受測者行走 6 公尺所花費的時間。

- 重複測試:建議進行 2~3 次測試,並取平均時間作為最終結果。

注意事項

- 測試時,評估人員要站在受測者後方半步遠的距離,這樣才不會影響走路速度。

- 如果受測者走路需要別人扶著才能走,就不適合做這個測試。

- 測試結果應以「公尺/秒」為單位記錄。

- 如果受測者需要拐杖或垂足板,要在記錄上註明。

- 測試中間可以讓受測者休息。

- 如果場地不夠大,可以改成測 5 公尺,但結果可能不會那麼準確。

記分方式

- 計時起點:當患者前腳越過 2 公尺標記時開始計時。

- 計時終點:當患者前腳越過 8 公尺標記時停止計時。

- 速度計算:以 6 公尺除以測試所用時間(秒)得出速度(m/s)。

- 若患者無法完成測試,記錄基線分數為 0 m/s。

4 如何解讀測試結果

- 中風患者

- <0.4 m/s:家庭步行者,建議只在家中走動

- 0.4-0.8 m/s:有限社區步行者,可以在社區中短距離走動

- 0.8 m/s:社區步行者,可以自由在社區中走動

- 健康老年人

- < 0.7 m/s:表示走路速度太慢,容易跌倒,而且有較高的住院風險。

- 健康成年人

| 年齡 | 男性 | 女性 |

|---|---|---|

| 20-29 | 1.358 | 1.341 |

| 30-39 | 1.433 | 1.337 |

| 40-49 | 1.434 | 1.390 |

| 50-59 | 1.433 | 1.313 |

| 60-69 | 1.339 | 1.241 |

| 70-79 | 1.262 | 1.132 |

| 80 以上 | 0.968 | 0.94 |

5 如何判斷分數的改變是否有意義

10 公尺行走測試的分數變化多少才算是有進步呢?我們會用三種方式來判斷:

- 最小可檢測變化(MDC):這個數字告訴我們,走路速度的改變是真的進步,不是測量時的誤差。

- 最小可偵測變化(SDC)或最小臨床重要差異(MCID):這個數字代表受測者自己能感覺到「我的走路變好了」的程度

不同疾病的 MDC 與 MCID

- 帕金森氏症(Hoehn and Yahr 分級 1-4,中位數為 2)

- 舒適速度 MDC:0.18 米/秒

- 快速速度 MDC:0.25 米/秒

- 脊髓損傷(不完全損傷,12 個月內)

- MDC:0.13 米/秒

- 中風

- 亨丁頓舞蹈症

- 前期(Pre-manifest HD)舒適速度 MDC:0.23 m/s

- 表現期(Manifest HD)舒適速度 MDC:0.34 m/s

- 早期(Early-stage HD)舒適速度 MDC:0.20 m/s

- 中期(Middle-stage HD)舒適速度 MDC:0.46 m/s

- 晚期(Late-stage HD)舒適速度 MDC:0.29 m/s

- 多發性硬化症

6 10 公尺行走測試的常見問題

1. 受測者走路的時候可以有人扶著嗎?

不行,一定要自己走得動。為了確保測試結果準確,受測者必須自己走路。

如果需要別人扶著,會影響走路速度,讓結果不準確。如果擔心病人會跌倒,評估人員可以站在受測者後面一點點的位置看顧,但不能碰到病人。

如果受測者需要人扶著才能走,分數就是 0 公尺/秒。雖然分數是 0,但還是建議要記錄下來當作基準分數。

如果真的需要人扶著走,要詳細記錄下來需要多少協助,以及走路的品質如何。這些資料對之後追蹤病人的進步很有幫助 (Salbach 2017)。

2. 如果受測者無法完成 2~3 次測試怎麼辦?

建議至少進行兩次測試,但如果受測者體力不夠或無法負擔,做一次測試的結果也可以。

3. 如果受測者做不到「一般走路速度」和「快速走路速度」兩種測試怎麼辦?

先讓受測者測試「一般走路速度」就好。

但如果受測者想要重返社區生活,就要特別關注「快速走路速度」,因為快速走路的能力代表病人能不能適應外面的環境,像是過馬路或在人多的地方走動。

等到受測者的狀況穩定,可以安全地快走時,就可以進行快速走路測試,追蹤他的進步情況。

4. 評估人員要站在什麼位置保護受測者安全?

建議在受測者的後方,距離半部的距離。

這樣不只可以在需要時及時保護患者,還能避免患者看到治療師拿著碼表而影響走路速度( Watson, 2002)。

5. 測試時患者可以使用輔具嗎?

可以使用輔具但要記錄,而且建議用病人平常習慣用的輔具,包含枴杖和垂足板 (Jackson, 2008)。

如果換了一個不熟悉的輔具,病人走路的速度可能會變慢或不穩,這樣測試結果就不準確了。

隨成病程發展,受測者可能改用不同的輔具或是不再需要輔具,每次都要記錄下來( Watson, 2002)。

7. 如果沒有足夠空間做 10 公尺測試怎麼辦?

如果空間不夠,可以用 5 公尺的距離來測試,不過 5 公尺測試的準確度沒有 10 公尺測試那麼高(Tyson, 2009)。

研究發現,短距離走路測試的速度,不能代表受測者走長距離的速度。

建議用 10 公尺這樣比較長的距離來測試,才有足夠時間加速到人們習慣的走路速度,可以更準確地評估,也比較符合日常所需(Huerta,2019)。

8. 要記錄受測者走 10 公尺用了幾步嗎?

看情況,記錄步數可以了解受測者的步幅大小。

不過,對於神經系統疾病的病人來說,目前還沒有太多研究支持記錄步數的重要性。

如果評估人員覺得對特定病人有幫助,可以額外記錄下來( Watson, 2002)。

7 影片示範

8 參考資料

- Academy Of Neurologic Physical Therapy

- Perry, J., Garrett, M., Gronley, J. K., & Mulroy, S. J. (1995). Classification of walking handicap in the stroke population. Stroke, 26(6), 982-989.

- Montero-Odasso, M., Schapira, M., Soriano, E. R., Varela, M., Kaplan, R., Camera, L. A., & Mayorga, L. M. (2005). Gait velocity as a single predictor of adverse events in healthy seniors aged 75 years and older. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 60(10), 1304-1309

- Bohannon, R. W., & Andrews, A. W. (2011). Normal walking speed: a descriptive meta-analysis. Physiotherapy, 97(3), 182-189

- Steffen, T., & Seney, M. (2008). Test-retest reliability and minimal detectable change on balance and ambulation tests, the 36-item short-form health survey, and the unified Parkinson disease rating scale in people with parkinsonism. Physical therapy, 88(6), 733-746.

- Lam, T., Noonan, V. K., & Eng, J. J. (2008). A systematic review of functional ambulation outcome measures in spinal cord injury. Spinal cord, 46(4), 246-254.

- Perera, S., Mody, S. H., Woodman, R. C., & Studenski, S. A. (2006). Meaningful change and responsiveness in common physical performance measures in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 54(5), 743-749

- Hiengkaew, V., Jitaree, K., & Chaiyawat, P. (2012). Minimal detectable changes of the Berg Balance Scale, Fugl-Meyer Assessment Scale, Timed “Up & Go” Test, gait speeds, and 2-minute walk test in individuals with chronic stroke with different degrees of ankle plantarflexor tone. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 93(7), 1201-1208.

- Tilson, J. K., Sullivan, K. J., Cen, S. Y., Rose, D. K., Koradia, C. H., Azen, S. P., … & Locomotor Experience Applied Post Stroke (LEAPS) Investigative Team. (2010). Meaningful gait speed improvement during the first 60 days poststroke: minimal clinically important difference. Physical therapy, 90(2), 196-208.

- Quinn, L., Khalil, H., Dawes, H., Fritz, N. E., Kegelmeyer, D., Kloos, A. D., … & Outcome Measures Subgroup of the European Huntington’s Disease Network. (2013). Reliability and minimal detectable change of physical performance measures in individuals with pre-manifest and manifest Huntington disease. Physical therapy, 93(7), 942-956.

- Nilsagard, Y., Lundholm, C., Gunnarsson, L. G., & Denison, E. (2007). Clinical relevance using timed walk tests and ‘timed up and go’testing in persons with multiple sclerosis. Physiotherapy research international, 12(2), 105-114.

- Paltamaa, J., Sarasoja, T., Leskinen, E., Wikström, J., & Mälkiä, E. (2008). Measuring deterioration in international classification of functioning domains of people with multiple sclerosis who are ambulatory. Physical Therapy, 88(2), 176-190.

- Salbach, N. M., O’Brien, K. K., Brooks, D., Irvin, E., Martino, R., Takhar, P., … & Howe, J. A. (2017). Considerations for the selection of time-limited walk tests poststroke: a systematic review of test protocols and measurement properties. Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy, 41(1), 3-17.

- Watson, M. J. (2002). Refining the ten-metre walking test for use with neurologically impaired people. Physiotherapy, 88(7), 386-397.

- Jackson, A., Carnel, C., Ditunno, J., Read, M. S., Boninger, M., Schmeler, M., … & Donovan, W. (2008). Outcome measures for gait and ambulation in the spinal cord injury population. The journal of spinal cord medicine, 31(5), 487-499.

- Tyson, S., & Connell, L. (2009). The psychometric properties and clinical utility of measures of walking and mobility in neurological conditions: a systematic review. Clinical rehabilitation, 23(11), 1018-1033.

- Fernández-Huerta, L., & Córdova-León, K. (2019). Reliability of two gait speed tests of different timed phases and equal non-timed phases in community-dwelling older persons. Medwave, 19(03).